Stanford Report

May 5, 2004

Encina Gym keeps on giving despite pending demolition

Crews salvage some materials from 90-year-old building

BY BARBARA PALMER

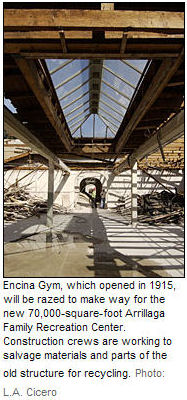

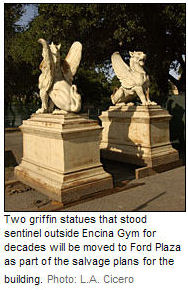

During its 90 years, the soon-to-be-demolished Encina Gym has seen generations of students pass through it doors, served as temporary storage for paintings and sculpture after the Loma Prieta earthquake rocked the art museum, and endured a radical interior redecoration when a wing was briefly home to the Stanford Band. But even as the walls of the 1915 gym are toppled this month to make way for a new 70,000-square-foot Arrillaga Family Recreation Center, the building has a few more incarnations to go.

During its 90 years, the soon-to-be-demolished Encina Gym has seen generations of students pass through it doors, served as temporary storage for paintings and sculpture after the Loma Prieta earthquake rocked the art museum, and endured a radical interior redecoration when a wing was briefly home to the Stanford Band. But even as the walls of the 1915 gym are toppled this month to make way for a new 70,000-square-foot Arrillaga Family Recreation Center, the building has a few more incarnations to go.

One thousand square feet of wood salvaged from the building is being used as flooring for a bar on Bush Street in San Francisco. More wood has been sold to a furniture manufacturer in Berkeley to make tables, and the roof decking that once held up red tile will be used as flooring in a house being constructed on Alpine Road.

The old tiles themselves have been removed and carefully stacked for reuse on other campus buildings, lengths of maple have been pried up from the gym floor, and a worker strapped on a safety harness and floated across the ceiling to remove light fixtures. (The maple will resurface at the new recreation center and next door at the Bakewell Building.) Dozens of windows have been removed intact, and more than a ton of remaining glass has been ground up to be used to make fiberglass. Sixty cubic yards of gypsum wallboard will be recycled as fertilizer.

As the building has been stripped to its rafters -- and then the rafters themselves carted off -- the project has come to more closely resemble a deconstruction than a demolition. Although efforts to salvage and reuse materials are business as usual on campus, the lengths to which project managers are going to reuse materials from Encina Gym is unprecedented, said Laura Jones, campus archeologist who served as cultural resources manager for the project.

Generally speaking, most demolition jobs turn building materials into splinters, said Dave White, an industrial hygienist who works for Environmental Health and Safety and is a member of a sustainability working group on campus. "The fastest way to tear down a building is to push it down, crunch it up, put it on a truck and send it to a landfill," he said. In addition to working toward campus sustainability goals, managers for the Encina Gym project also were required by the county to salvage as many architectural elements from the historic building as possible.

'An eccentric, very special kind of building'

The university had studied ways to reuse the gym for years before asking the county for permission to tear it down, said Jones, who has worked to document the building's history. Originally built as a men's gymnasium, it was designed by John Bakewell and Arthur Brown Jr. of San Francisco. It was the second campus building to be designed by the pair, who designed many Stanford buildings, including Branner Hall, Roble Gym and the Bing Wing of Green Library.

The university had studied ways to reuse the gym for years before asking the county for permission to tear it down, said Jones, who has worked to document the building's history. Originally built as a men's gymnasium, it was designed by John Bakewell and Arthur Brown Jr. of San Francisco. It was the second campus building to be designed by the pair, who designed many Stanford buildings, including Branner Hall, Roble Gym and the Bing Wing of Green Library.

The original gym was expanded so often that it eventually contained six different sections, said Jones, who herself used the gym as a graduate student. "Every time they raised more money, they built another wing," she said. The result was an "eccentric, very special kind of building. It was charming but inefficient in every sense of the word."

When White, wearing boots and a hard hat, shows visitors around the demolition site, his deep affection for the old building and respect for its original builders is palpable. "Nobody can do that anymore," he said, sweeping an arm toward a masonry arch, uncovered when the wallboards were peeled away. "The workmanship is so beautiful," he said, pointing out building details including crown moldings, decorative brickwork and ceiling rafters constructed of rough-cut timbers. He shows off bundles of twisted aluminum and stacked pipe with the satisfied manner of a frugal housewife happy to be using up every bit of the Thanksgiving turkey. (In one room, where White oversaw the removal of asbestos, "when we were finished, the floor was so clean you could have eaten off of it," he said.)

White has been working closely with Jim Steinmetz, owner of Reusable Lumber Co. in Woodside, which specializes in dismantling structures and reselling timber, fixtures, and doors and windows. Steinmetz worked as an environmental activist after graduating from Sonoma State College with a business degree and supplemented his income by working part time as a carpenter. "A lot of the work was knocking down homes to build more dream homes," Steinmetz said. His seven-year-old company supplied the salvaged redwood siding that was used at the field station at Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve.

Steinmetz and White celebrated Earth Day on April 22 by filling a truck with 20,000 board-feet of lumber from the gym, enough to build an average-sized U.S. home. "If you think of recycling as a pyramid, reuse is at the very top," Steinmetz said. The "fantastically thick" wood that came from the roof of the old gym is of such high quality that it's not sold on the open market anymore, he said.

The university has agonized over the fate of the building, White added. It's a consolation to be saving some of it, he said.